Breaking the Record

I’m standing on the crest of a gentle slope, in the west.

I shade my eyes as I squint down a long stretch of highway, and I see nothing on it, nothing but the gentle, pink sun, sinking low in the horizon and warming my naked chest. I am alone, standing in the middle of the road, except for the crickets in the weeds, the trees, and the cows in pastures all around me. I feel nothing but a sweet summer breeze that fills my nose with a soft bouquet of flowers, corn, and June hayfields.

Beside me, my motorcycle is parked on its stand in the middle of the highway. It would make a fine photo. Have you ever lain in the middle of a deserted road, put your head back on the hard tarmac, just to see what it feels like? There is no describing how wrong the sensation is. You look up into the sky, and want to get off it as quickly as possible. The only things that are lying down on a highway are dead.

I turn east.

Ahead of me lies a length of soft, new pavement, put down and painted only a few weeks before. It’s perfectly straight, coal-black and immaculate in the fading light of the dusk, running two kilometres past the home I grew up in. At the end of it is Jon, who is watching for traffic coming from the other direction. I’m waiting for the “all clear” signal.

Half an hour ago, we installed washers on the gas tank of my motorcycle. See, the air intake is right beneath the tank cover. An engine needs air to burn gas. The more air it gets, the more gas it burns, and the faster it goes. So we grabbed a handful of washers out of one of my dad’s rusting coffee-cans, and put them on the bolts that hold the cover down, which raised it above the intake by a good inch or so. Without the tank cover blocking the way, this gaping, one-inch mouth should allow my intake to suck down the air like a galloping racehorse.

In theory, anyway. The entire exercise reminded me more than a little of putting old O-Pee-Chee hockey cards with clothespins on my bicycle spokes, so that they’d make a motorcycle sound when I pedaled down the road. I did that fifteen years ago in the same garage.

“With more air, maybe the bike will go faster,” I said to Jon. I wasn’t too sure about it though.

“How fast?” he wondered.

“I don’t know. If I’m really lucky…maybe ten clicks faster. I’ll have to try it out.”

Ten kilometers per hour more, that would be fantastic. The fastest I’d ever ridden the bike was 235 kilometres per hour, down this same stretch of highway last summer.

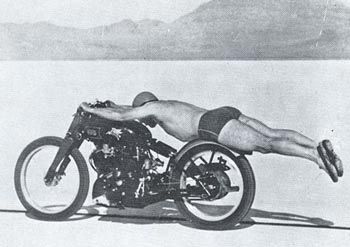

I saw this photo once, when the motorcycle land speed record was set on the salt flats outside of Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1948. In those days, the bike everybody talked about possessed a name as elusive and mysterious as its own legend:

The Vincent Black Shadow.

One day in 1948, a motorcycle racer named Rollie Free took his Shadow to the salt flats with the goal of setting the world-record speed for a motorcycle. He wanted to take it all the way up to 150 miles per hour, which would easily shatter the previous record of 136, should he accomplish the mark.

But despite a specially-tuned bike and numerous test runs, the fastest Free could push the Vincent was 148. This was good enough to break the record, but he wanted 150, and he couldn’t do it.

That is, until he decided to try something different.

After multiple, tortuous, high-speed runs, Free’s leather riding gear had actually torn open along the seams, scooping air and resulting in excess drag on the bike, hindering his attempts to break 150. And besides that, the gear was heavy. So before his final run, Free stripped off every stitch of it, and put on a pair of skin-tight swimming trunks, a shower cap, and some borrowed shoes.

The next thing he did was start up his Vincent, and take off down the flats for the last time, clad only in his Speedo swimsuit, working his way through the gearbox until he had topped out in the highest gear.

Finally, with the gas open all the way to the stop, he stretched his body out on the gas tank of the Shadow, putting his legs up on the seat behind him, with his feet hanging off the back of the bike in the slipstream – lying on top of the Vincent in exactly the same position that Superman might, flying in his legendary way above the streets of Metropolis.

He was doing this - with his nose pressed kissing distance from the gas tank, arms stretched out like a kid on a jungle-gym, and his toes pointed behind his bike to decrease every possible inch of drag- when a photographer snapped a photo of him. Rollie Free blew past the photographer that day at 150.31 miles per hour, setting the world-record speed for a motorcycle that would stand for twenty years. It also cemented the reputation of Vincent HRD Motorcycle Company in riding legend for all time. It was one of the most sensational stunts ever pulled off in the history of motor sports, and the black-and-white photo of Free, rocketing across the flats in his bathing suit, remains the most famous motorcycling picture ever taken.

Over fifty years later, I'm standing on a highway in my shorts, shirtless, gearless but for my helmet, about to make my own attempt at a top-speed run in nearly the same matter that Free did. I’m thinking about that photograph, wondering what Free must have been considering before he performed his lunatic stunt.

I know what I’m thinking. I’m thinking that, at the speeds I’m hoping to reach, it won’t matter very much that I’m wearing no gear if I wipe out. I’d probably just blow up like a watermelon all over the road.

I'm also thinking, I'm glad I didn't tell Dad I'm doing this.

Stupid as hell? Oh, yeah. But that isn’t going to stop me. When you own a motorcycle, there arrives a day when you have to light it up just to see what happens. For me, that day is today.

Across the valley, the headlights of Jon’s own motorcycle flash, on-and-off, on-and-off:

All clear, man.

I want this run to be absolutely as fast as I can go. The conditions are perfect; I’ve got a nice long, gentle grade to ride down, no traffic or other distractions to enhance the dangers, and a helpful breeze pushing at my back. And I'm not going to let those things taint the speed I'll reach - nobody remembers advantages like that, only the final number on the scoreboard. I have my fairing to shield me from the hurricane-speed winds I'll encounter, and I’ll be pressed against that bike like a coat of paint. How fast will I go?

There’s only one way to find out.

I swing my leg over the bike and thumb the starter. My V-twin burbles to life through its gleaming race-pipe - the same engine design as Rollie Free's Black Shadow. I gun the throttle a couple of times in preparation. There is nothing in the world that sounds like a V-twin thundering through a glasspack exhaust; nothing. I look behind me one last time to confirm that, no, there aren’t any cops coming up the road. I slap down my visor and punch the bike into first.

The motorcycle jumps from the tarmac, the exhaust blatting angrily behind me. I drop it into second gear almost immediately, then into third. In only three seconds, I’m past the maximum legal highway speed, a human bullet aimed at the end of the valley. Jon’s headlight is the beacon of a distant star, still flashing, “all clear.”

Into fourth, and the bike wrenches beneath me with muscular torque as I make the change, the engine continuing to cycle up between my knees. I can hear the sound of the intake, freed by the lifted tank-cover, honking as it gobbles the summer air. I look down and I’m already passing 160 kilometres per hour.

Ahhhhhhhhhh…

Fifth. The engine is now a full-blown, nasal bellow, open nearly all the way, filling the valley with its Spitfire roar. The needle passes 200. But I know there is some left.

AHHHHHHHH…

Sixth gear. That's it for the gearing; I slide back on my seat, squeezing the bike with my knees, imagining myself flatter than a film of dust on the back of my bike. I flick on the high beams with my thumb, rest my chin on the gas tank, and twist the throttle to the stop. I think of Rollie Free, with his bare face pressed to the glistening black paint of his Black Shadow, flying across an endless field of salt, sparkling in the sun like new-fallen snow.

BWAHHHHHHHH...

Trees and fence lines are blurring past, and birds are startled into flight by my passing. My eyeballs vibrate and tear up inside my helmet as the bike races to reach the end of its legs. It’s still accelerating, but now approaching the limit of its capabilities. Jon is now no farther than 200 metres away. A sudden sandstorm of blackflies ticks into my visor. Finally, I sense the bike arriving at the nadir of its speed, and I flash a quick look down at the clocks.

The tachometer needle is swung all the way over to the red, past 10,000 rpms. The speedometer is buried just over 240 kilometres per hour.

I come out of the sun, and I see Jon raise a fist and whoop as I burn past him, a faint sound that is behind me as soon as I hear it.

And for one last moment, I relish the overwhelming sense of rocketship power, the sensation of flying at ground level. The gleaming, jellybean red of my bike makes me feel like I’m hanging for dear life onto the back of Superman’s cape, and I take in the feeling of a motorcycle engine spinning beneath me, extended to the very limit of its powers. I feel like I can go anywhere, anytime, as fast as I want to. I finally close off the gas.

BWAAAAHHHHHHHHhhhh...

I’ll probably never ride so fast again in my life.

I sit up on the seat, catching the air with my chest like a human parachute, feeling the tornado warmth of summertime air rushing around my body and pushing me back to earth, the speedo rolling back...200...180...120...80. Now I'm rolling at a sane highway speed, and I’m almost convinced I can hop off and jog faster than I’m riding.

I turn around and idle back over to Jon, parking beside his bike. I kill the engine.

“How fast?” he says.

“The needle was past 240...maybe about 242,” I say.

“242? Holy shit,” he says. He pulls my calculator out of his pocket and does the math. 242 x .62.

“That’s 150.04 miles per hour,” Jon grins in the gathering twilight.

"150. The old record," I say.

I think about ancient, front-page photos of men in bathing suits who once rode spindly old motorcyles to bust 150 miles per hour, and how they became kings because they did it.

Around us, the crickets chirp louder in the failing light, and no cars pass to break the spell.

3 Comments:

you are a king.

among men.

Fine post! I was riding with you all the way. You captured that exhilerating sensation of speed. A biker knows about these things!

Post a Comment

<< Home